Body status: No longer fit for purpose

In true influencer style, I picked up Primate Change after hearing an interview with Vybarr Cregan-Reid on my favourite podcast, Sustainababble. I’ve subsequently read both his books, and heard him speak at a conference late last year. He also liked one of my tweets a while back – therefore, I am a fan.

Cregan-Reid chews on all of human history in chronological order in this book, subtitled How the world we made is remaking us. It could easily have been a drag to digest all 299 pages but instead it was entertaining, captivating and dare I say it life changing.

In a nutshell, for around 2.3 millions years we were nomadic hunters, then for a few thousand years we’ve been settlers. In the last hundred we’ve become tech-savvy shoppers, this book explores how our bodies have coped with these huge changes in our environment.

Cregan-Reid charts the evolution of Homo Sapien Sapien, briefly touching on our ancient cousins from our upright posture and hip joints to our changing diet; leading to all sorts of dentistry issues and even changing the shape of our faces! He covers the implications from the agricultural revolution, a period of 4000 years when we decided to stay put, to snacking. And the outsourcing of our labour to the animals we had domesticated, to slaves. Consequences of which meant a systemic laziness for the wealthy leading to the concept of ‘exercise’, so the elites were still fit enough should they need to go to war.

Fast forwarding to the Industrial Revolution when many of our ancestors had relatively stationery jobs and children as young as 5 working repetitively for long hours, in dangerous working conditions. It also coincides with reports of flat-footedness, hay-fever and spine deformities.

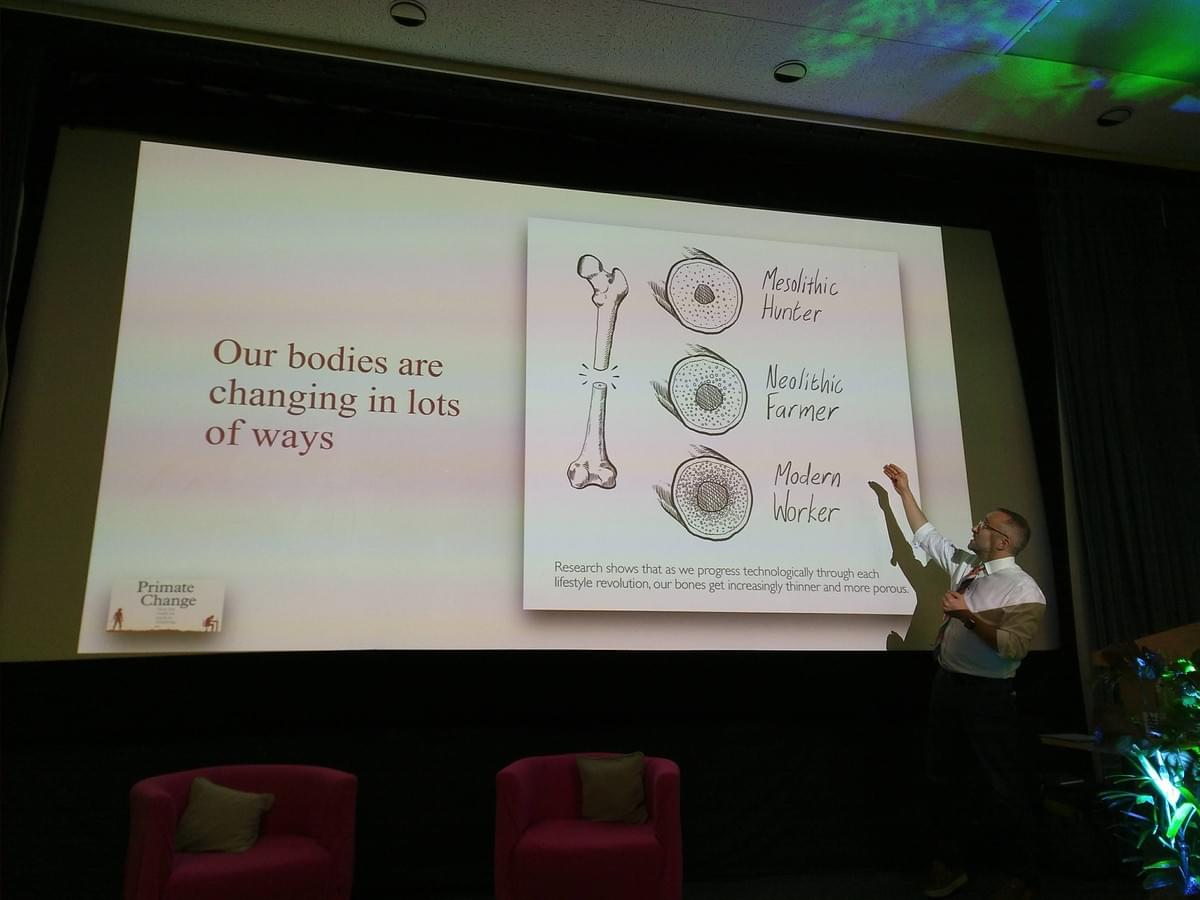

As we emerge into a more familiar world of work or the “sedentary revolution” of the 20th century, leading to the “biomechanical domino effect of office life” and the tilting pelvis. Complete with illustrations, we learn just how much we’ve changed our surroundings and in response how our bodies have changed, mostly for the worse. He highlights just how dangerous our sedentary lifestyle (work and sedentary leisure, think cinema, pub, eating out etc) is;

“Every two hours we spend sitting…reduces our blood flow, lowering blood sugar and increasing the risk of diabetes, obesity and heart disease.” Importantly Cregan-Reid points out, “you can exercise and still be classed as sedentary because of the sum of the hours you spend sitting.”

Back pain is so ubiquitous in today’s society; “lower back pain is now the single most leading cause of disability throughout the world. It is the most common reason for missed days of work. It is the second most common reason for visiting a doctor.” And yet Cregan-Reid points out, our ancestors were lifting freshly caught predators, doing tough manual labour and we are getting back pain from just holding ourselves upright! ♀️

He goes on to talk about ‘mismatch diseases’, “thought to be brought about by the tension between our bodies and the newness of the environment that those bodies are required to inhabit”. These diseases include Type 2 diabetes, asthma, osteoporosis, lower back pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, generalised anxiety disorder, myopia (short-sightedness), overcrowded teeth, RSI, eczema…

“Our idea of what our bodies are capable of is warped,” Credgan-Reid added at the Communicate conference late last year. Did you know our bone density of our ancient farmer ancestors was “30 percent stronger than those of non-athletic modern women”?

Throughout the book Cregan-Reid highlights that “we have repeatedly mistaken what is comfortable with what is best for us, what is ideal for that which is quickest or easiest, and what feels good for what is good for us.”

It has been really tricky deciding what elements from the book to pull out in this post, essentially every human would benefit from reading this. Here are three more elements that really stuck out for me:

Calling BS on “I think therefore I am”

It’s worth considering, what do we use this body we have been given for? Thousands of years of evolution went into designing this near perfect specimen and what is it used for?

Well currently, consuming a LOT of chocolate digestives (#CoronaLife). Sat for hours in an unnatural but conditioned comfortable position, using my eyes to stare at an illuminated screen just over 12 inches away from me.

I’ve prioritised my brain over my body for a long time. I would argue that even my schooling prized my cerebellum over my feet. Two hours of PE every week that I was often trying to get out of with the longest standing period ever!

I’ve had issue with Descartes, “I think therefore I am” slogan for a long time. And recently, a wonderful woman wrapped words around my frustration with it. I’m paraphrasing activist Mama Ujuaje here: Descartes decapitated us that day with that statement.

I’ve even noticed it in phrases from Youtuber Yoga With Adrienne; “connect the mind intelligence with the body intelligence.”

And then Cregan-Reid reframed it for me in straight forward language: we have a brain because we have a body, not the other way around. (Well duh! but really this was happening: )

The invention of the humble chair

Have you ever taken a moment to look at your nearest chair? Have you ever counted how many chairs you have in your house? Something so ubiquitous I’d never questioned life before the chair, or when they entered our lives in such numbers.

Cregan-Reid invites us to count not only the chairs we own but all the chairs we might have sat on in one day; the bus chair, the office chair, the doctor’s waiting room, the driving seat…boy we sit on a lot of chairs.

He estimates there are approximately 52.5 billion chairs – and heralds them as the symbol of the Anthropocene. They can be found everywhere, on land and discarded on the sea floor. We look back in history and learn that the chair was the symbol of high status, reflected in our language today, consider chairman of the board? The chair was in time democratised with increased modes of mass production of the Victorian age. Cregan-Reid points out that ‘chair’ is not mentioned once in Hamlet but by 1851 “Dicken’s Bleak House…they are mentioned 187 times.” 1960s injection moulding meant the chair were everywhere not long after that.

The sedentary lifestyle came into existence in the Industrial Revolution but poignantly points out, from our schooling system, “perhaps the greatest contributor to emerging sedentary life was the way we trained and recruited our children into it too.”

I’ll never hear the command “Sit down” or Sit still again! Fidgets among us, rise up and deny the chair its muscle and posture degenerative power!

My two current favourite chairs, seductive little things!

Climate Change Food

I’m pretty clear on the climate science these days but what I had not considered was the impact increased atmospheric CO2 has on our food. CO2 is needed for photosynthesis but what is the impact on the equation with a lot more CO2? Here’s the science-y bit, word for word from Cregan-Reid. “If plants draw CO2 from the atmosphere but draw almost all other chemical elements from the soil does a problem arise because the rise in CO2 in the atmosphere is not paired by a perfectly-matching equivalent enrichment in the soil?… As extra CO2 in the atmosphere pushes the accelerator pedal for the production of glucose in the plant there is no equivalent acceleration of nutrient uptake. This suggests that there maybe a global elemental imbalance that could have an impact on chemical elements such as “iron, iodine and zinc, which are already deficient in the diets of half the human population.”

Cregan-Reid cites a 2014 study by Loladze, showing that rising CO2 consistently lowers the quality of plants, we get more carbohydrates and starches, meaning “we’ve sacrificed quality for quantity.” Loladze estimates an 8 percent drop in nutrient levels, dubbing it a “nutrient famine.” This leads to “compensatory eating”, eating more to try and get the nutrients we lead, Cregan-Reid makes the link with the obesity epidemic and referencing a study showing that “humans are not the only species gaining weight in the Anthropocene.”

Had to put the book down for a while and think this one over.

Take it back now y’all

Like all the awesome books I’m reading at the moment, there are strong calls to action.

Wary of nostalgia, Cregan-Reid isn’t suggesting we return to the stone age and acknowledges the all the benefits that come with a life not threatened by sabre-tooth tigers.

But at the end of each section he suggests a few nuggets from historical eras that it might be worth winding back to. Here are just a few highlights:

- Consume more vitamin D and “Vitamin N” i.e. nature.

- Chew some more – to stimulate mandible bone density

- Brisk walking and running are good for spine and knee health

- Avoid hibernation – i.e. activities that “normalise sitting for extended periods of time”

- Feed your gut as well as yourself

- Lift your pelvis

- Try to go barefoot more often – “so the intrinsic muscles in your feet are allowed to respond”

- Make a stand against sitting and consider a different working environment

- Most important of all: walk!

Taking his own advice Cregan-Reid “has tried to shake the idea that the best place to work is at home. Now, on an average day I will write in at least 3 different places; one of them is always home, but the others are usually spread out over a few miles and I work between them. So, I now walk 64-80km (40-50 miles) a week and it feels like nothing. It’s easy: I don’t feel tired; it has kept me sane.”

What’s one more crisis?

In evolutionary terms, we have changed our environment so rapidly, in the blink of an eye.

“As a result, our bodies are in shock from these changes. Modern living is as bracing to the human body as humping though a hole in ice. Our bodies are defending and deforming themselves in response.”

Is this a movement crisis? I asked Cregan-Reid at Communicate. I mean since we’re in a climate, ecological and social crisis and right this very moment a health crises – why not throw one more into the mix?

Physical inactivity “contributes to a mortality burden as large as tobacco smoking.” Of the top 10 ranked causes of “years of life lost + years of disability” published by The Lancet, 7 of them are to do with diet and movement calling it a “public health priority.”

And you’ll never have guessed it, they’re all interlinked. Increasingly intensive agriculture to feed a growing population, an economic system ruled by oligarchs has processed food more affordable than fresh food, exercise and leisure has been commodified and is often considered a luxury, and a gig economy has us slaved over a laptop for hours at a time for fear of losing job security and a climate with more carbon in the air reducing the nutritional value of all the food we eat.

Whatever the multi-level, multi-stakeholder solutions are to the climate, the economy and society – can we embed a culture of movement as well?

Stop reading and move

At various intervals throughout this book, I made a lot of commitments to myself that I would move more. In fact a few times, I just put the book down and took myself out for a walk. I began seeking out cafes that were further away so I needed to walk further and deciding that a bike wasn’t a priority as where I’m currently living everything was walkable. For a good few weeks I was building up to 5 days out of 7 where I was walking more than an hour, even purchasing waterproof trousers so I couldn’t use rain as an excuse. I was powering through audiobooks and noticing my mood improve. I was set on a trip to the Brecon Beacons where we walked minimum of 4 hours for 3 days, I like to think of it as a walking-bender or binge-walking.

Proof: view from the bottom and the top

Then coronavirus restrictions happened, and anxiety overrode my good intentions. So here I am, sat on my arse most of the time, again, restricting blood flow and shortening my hip flexors. ♀️

Having taken the time to write this though under the guise that it might be useful for a few of my readers I have reminded myself of why I had pushed movement up my agenda. So, it’s back to the long walks I go, even if there’s no useful destination. My body is worth that much.

I wonder how Vybarr’s holding up with these restrictions?

Aside

The song running through my head while reading this book